In the hot, summer month of April, I found myself coming home to a quaint house, the transported childhood home of my Mother. Inside the house was the memory of my youngest Tita, Tita Nene Grace, cooking escabeche in the kitchen.

At the time, she was a sophomore in college, taking up Political Science at Central Philippine University. For a while, we stayed at my grandmother and grandfather’s house, while Papa and Toto Carbon—not yet a Pastor that time, but who decided to journey with us from Davao del Norte, and who dedicated his life into full-time ministry—were tasked to build the second reiteration of our house at Mama’s inherited parcel of land.

During our free time, Tita Nene Grace and I would complete relatively large jigsaw puzzles. I remember, we worked on a complicated landscape of a picture of vines and flowers and a house. Other times, as we did not have a working electricity at our newly constructed house, we would also spend our time watching TV at night, when all the tasks were done—like fetching water to and from the poso, or in Hiligaynon, bomba gathering firewood from the vast acres of land, and cooking meals for the family. She emphasized early on how to relax and have fun, when all the house chores were checked off.

As an adolescent, at a time when there was no Internet connection yet, no Friendster, no Facebook, and no YouTube yet, our pastime were mostly spent at watching the television, especially on Sundays after church. The family would bond over ASAP, and even towards Tabing Ilog. LOL.

Most importantly though, our Sundays were always spent at church. I grew up with women who made it a point to sacrifice their time to worship Jesus on Sundays. There was even a moment when I was absent from church because I went with Tita Lourdes to help in their carinderia, that Mama reminded me of Colgate’s (yes, the toothpaste brand) story—the emphasis of which was to seek God first on Sundays, and throughout one’s life. After that story, I made it a point that even if I helped with Tita Lourdes in their carinderia during Saturday and Sunday, I would go home early Sunday and go to church with the family.

When I was in high school, and I quietly decided to stay at my grandmother’s house, while our entire family moved to Antique for a pioneering work in one of the southern coastal towns, Tita Nene Grace would help me in my Greek and Roman Gods and Goddesses assignment. We had no Google back then, but she owned a gigantic encyclopedia, and we would research together the names of the Greek Gods and Goddesses. In a way, Tita Nene was instrumental in my desire to excel in my classes because she would come home with college friends like Anne or Loren (of which the only ones who I could remember), and I would talk to them for hours about their lives as university students. I would sit with wide-eyed wonder and my brain would just listen intently while her college friends would talk about their travails and their experiences in taking university classes. One of her college friends, a reader, introduced me to The Bridges of the Madison County, and it was probably one of the reasons why I was encouraged to read voraciously.

But my love for reading did not start when Tita Nene Grace would come home on weekends together with her college friends. As a child, I already had an affinity towards books, as revealed by Manang Ging-Ging Escobar. Talking to Tita Nene’s college friends affirmed my love for books, and the life-changing experience that one goes through as readers journey through the life, or death, of the book characters.

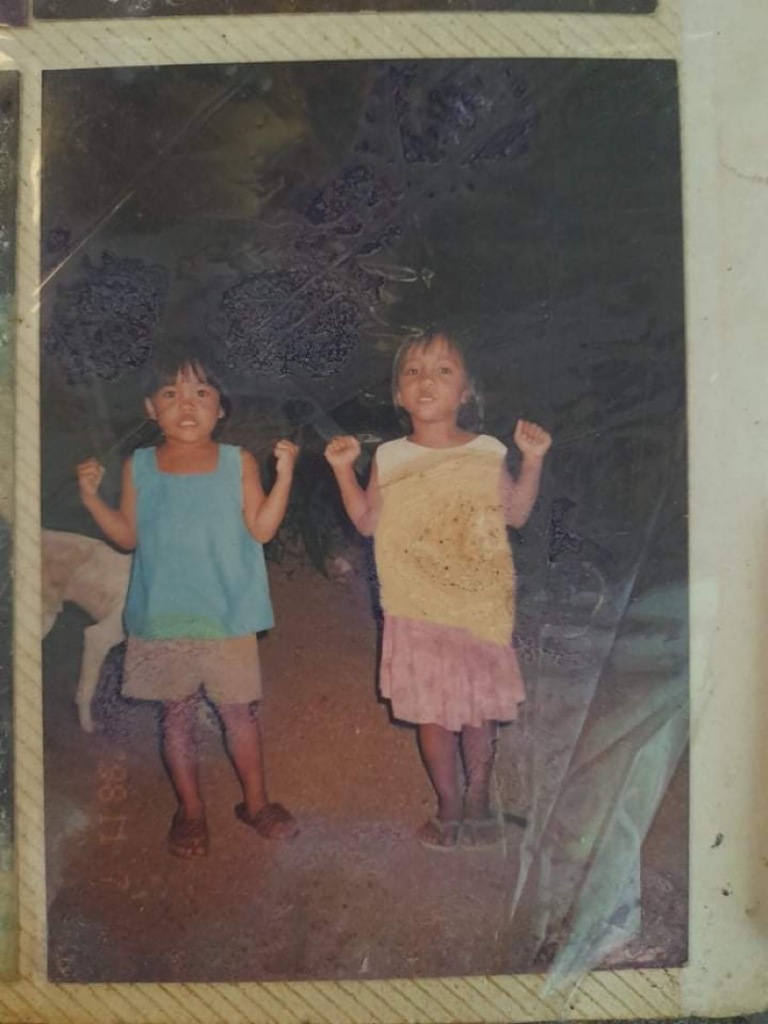

Interestingly, Tita Nene Grace was one of those who were put on a pedestal by a lot of people in the family because of her wit and beauty. She joined pageants and there were pictures upon pictures as proof that she won these pageants. She was also the school’s declamation champion, trained by, as far as I could remember, Ma’am Patricio, who I met briefly when I transferred to Millan Elementary School, from Fundamental Baptist Christian Academy in Davao del Norte.

I also followed Tita Nene Grace’s footsteps, even though my background was oration, and won the municipal literary contest for English Declamation. I would often practice in front of my relatives, including Tita Nene Grace, as one of the de facto coaches. I did not place in the provincial literary and musical contest, but I could not care less. I’m not sure what classical conditioning did I receive from my relatives to be able to expose myself to stage fright and to nerve-wracking situations, but as long as I had my parents as my cheerleaders and supporters, I would take the stage.

Aside from being an achiever, one of the most noteworthy characteristics that Tita Nene Grace exemplified in her life, was her steadfastness and conscientiousness in her personal duties as a person and as a member of the church. I loved spending time at church when I was starting my adolescent years, because we would visit church members and we would have Bible studies, together with my cousins and my Titas. She made it a point to exemplify what Matthew 6:33 meant.

But the journey called life was never a walk in the park—there were also challenges and boulders that we faced as a family. As someone who experienced outright rejection from my grandfather, after I tried to take his hand to “mano po”, there were also moments when I witnessed Tita Nene be caught in between these familial conflicts. There was a time when, weeks after arriving at Talangban from Davao del Norte, I saw Tita Nene Grace talk to Lolo Oyo. After a while, she locked herself in her room on the second floor of the house and, I felt at that time, that she wept in silence.

There were also moments when I came home from volunteer work with Save the Children that the family, including He-Who-Must-Not-Be-Named, were gathered, and were discussing complicated things. It felt very awkward for me while I was listening to this certain visitor talk about her opinion and her point because she seemed confrontational and crass. As a minor, and as someone who was not part of the conversation, I sat there in the huddle, in support of my Aunt, my Mother’s youngest sister, whom I felt during that time, was being verbally attacked.

In the many milestones that I had, from graduating Valedictorian in grade school, to finishing Salutatorian in high school, Tita Nene Grace’s presence, together with Pastor Gideon, was felt and, at the same time, seen. She was always very supportive with her nieces and nephews, and I for one, am very blessed to have seen her never waver in prayer and support to all of our dreams.

I’m actually glad, and blessed, that I have access to her, and that I can share with her my, our struggles, as a family and as a person. From solving jigsaw puzzles as a kid, to reading thrillers, then listening to easy-listening music, and ministering in whatever way we could, growing up with someone to look up to and someone whom I could aspire to be like, made my life more meaningful.

In the two deaths that we experienced as a family—first, my grandfather Lolo Oyo, and second, Mama Melanie—we never made it a point to be ashamed of our tears. Although the family dynamics were affected when we lost Lolo Oyo and Mama, we understood the process of our grief and we respected each other’s moment in the storm.

There was even a time when it was hard for me to understand the ripples of events that were created after Mama’s death, and that I was grasping for someone’s beacon of light and guidance, that Tita Nene Grace and Pastor Gideon came rescuing with the Sword of the Spirit, “which is the Word of God”. They emphasized that in God’s grand design, respect should still be given, even though we do not comprehend the actions anymore.

For what it’s worth, I am actually very proud that I get to call Tita Nene Grace, my Tita, as cheesy as it may sound. More than the pedestal that she was put in—her being an achiever and role model, her conscientious and steadfast stance on duty towards family, and her genial and conciliatory approach towards her relationships with those around her—it is because of her genuine love towards others, and even to us her family first, and her undying devotion and love for Jesus, the Author and Finisher of our Faith, that I appreciate the very life that she lives.

I do understand the struggles and the joy of serving in the ministry as a Pastor’s Wife, because I have seen the example and the magnificent story in the life of Mama as a minister of grace. And with Tita Nene Grace, her name Grace, is the very definition of her and mine, our, salvation—unmerited favor.

We do not deserve, and I do not deserve, Tita Nene Grace. But her life is a testament that when everything points towards the pursuit of intentionally knowing Christ, our lives become blessings to the very people around us, including our families. After all, what is life but a mist—it appears and then it’s gone. Such is the brevity of life.

Despite life being short, I’m glad to have memories of and with Tita Nene, in this lifetime.

*Blessed Birthday, Ta!

*Thank you for teaching me the true meaning of purpose and passion. Through your life, I have found these, only in Christ alone. #